In this time of COVID, we are flooded with unanswered questions and a profound sense of not knowing what is next. What will be the “new normal?” Nurses and other health care professionals have expressed feeling that they are in a bubble when they are providing care because of the complexity and enormity of what they must do. The degree of grief and loss they are witnessing is on a scale that they never imagined they would experience. Through all of this, it is vital for us to know that despite all this, we have resilience and the capacity to learn, grow and heal as we go forward.

It is important to take a moment to reflect on what brought you to work in a health care setting and profession. Often, the reason for that choice is barely recognized or remembered. What moved you to care about others and want to help?

Working in this time of COVID brings back memories of my clinical practice in the early 1980s when a mysterious disease appeared that was causing illness and death. My practice was in Greenwich Village in NYC. This was a neighborhood that had a significant population of homosexuals.

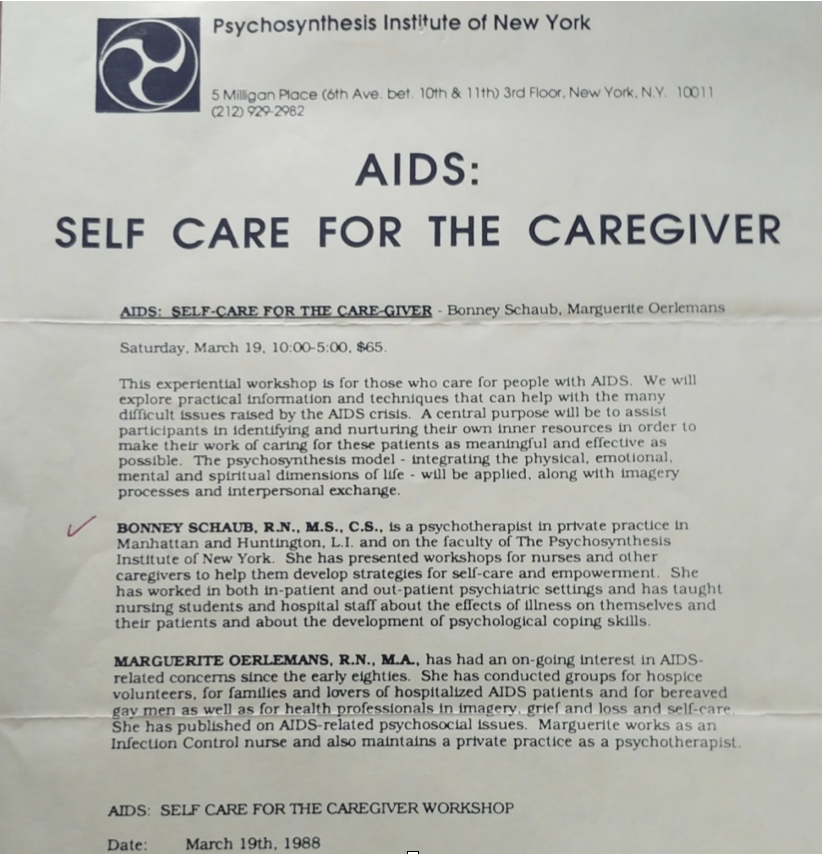

I was one of the founders of the Psychosynthesis Institute of New York, a pioneering transpersonal psychology that offered a mind/body/spirit model of the person. This work integrated meditation and imagery practices into the model of care. I was known for bringing these practices into my clinical work.

New York University’s nursing program was integrating a holistic model of care, and some of their nurses were interested in learning about my work for their own well-being and to bring to their patients. At that time, the nurses were beginning to care for AIDs patients, and a student/nurse colleague of mine, Marguerite, was deeply focused on these patients.

In addition to the deep fears and medical challenges that her patients were personally experiencing, they were also flooded with grief and bereavement because of all their friends who had died. Many of them had been rejected by their families and had moved to NY for this very reason. Their AIDS-related bereavement was “socially unspeakable” because of their jobs and other life situations where being gay would have been unacceptable.

In the bereavement groups, Marguerite integrated meditation and imagery practices to assist the members to connect with a peaceful state within. The work helped them to observe their pain and but also feel the love which was still present even without the physical presence of the loved one. As a group, the participants were able connect with their inner strength and wisdom and honor this presence of love with each other. It became a way of imagining moving forward and deciding what was important and of value.

Marguerite and I knew the importance of sharing these practices with our colleagues so we created training and support groups to teach our transpersonal mind/body spirit approach.

What I experienced and learned in this work was the possibility of coming through this suffering feeling capable of being healed physically, emotionally and spiritually. The care givers learned to trust the fact that deeper wisdom is a natural part of each of each of us. The patients, in becoming able to connect with their inner knowing, were able to make choices that led to living a more fulfilling life. There are a number of people I am still in contact with today. They have chosen to work in a variety of creative and helping ways as they discovered their soul’s place in moving forward.

This work provided me with dramatic evidence of the strength of bringing a transpersonal perspective into my clinical work and the training I provided to others.

Marguerite Oerlemans-Bunn: On Being Gay, Single, and Bereaved. Amer. Jnl. of Nsg. Vol. 88, No. 4 (Apr., 1988)

An ad for a workshop we conducted in 1988.